In writing this post, I may be crashing the American Psychological Association’s annual blog party. Naturally, I’m in favor of joining others to increase awareness and reduce stigma around psychiatric problems. But despite the spirit of solidarity, I’m perhaps an outsider, because I no longer believe ‘mental illness’ serves as a helpful concept.

In writing this post, I may be crashing the American Psychological Association’s annual blog party. Naturally, I’m in favor of joining others to increase awareness and reduce stigma around psychiatric problems. But despite the spirit of solidarity, I’m perhaps an outsider, because I no longer believe ‘mental illness’ serves as a helpful concept.

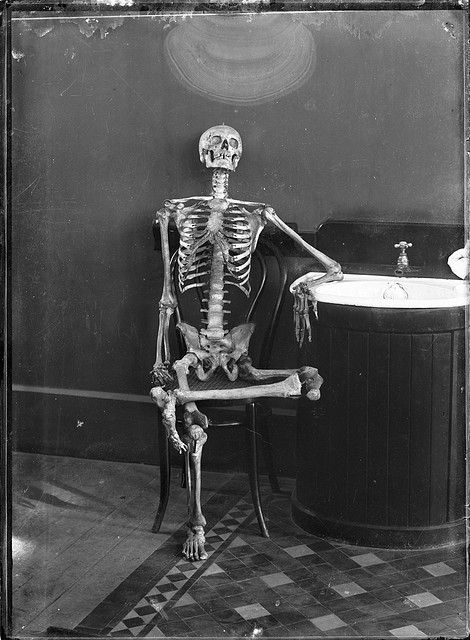

In this era of burgeoning diagnoses, it’s a bit awkward to declare our great emperor, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), naked and unfleshed. Especially at a party.

Let me be clear: people sometimes behave in ways that look incomprehensible or even insane. Suicidal behavior, profoundly delusional speech, and irresistible compulsions represent severe behavioral problems for individuals and society. No doubt they stem from cognitive activity and emotional tones that differ from average day-to-day awareness. These sorts of disordered conduct do indeed derive from ‘mental’ processes, but do they qualify as ‘illnesses?’

It seems to me that to define something as a disease implies that we can also recognize its absence. But this isn’t always easy with mental conditions. Take the example of suicide. Frank attempts on one’s own life lie at the extreme end of a spectrum of self-destructive thoughts and actions. Some of these get labeled as mental illness, and some don’t, but the distinction is rather arbitrary.

I suspect a majority of the population would have to admit to moments of wondering if life is worth the effort, and to brief thoughts of ending it. We aren’t mentally ill just because we have moments of doubt. How frequently or how seriously does a person have to question life’s value in order to be deemed sick? Or consider that a man with advanced emphysema who continues to smoke kills himself just as surely as a woman who takes an overdose of pills. But our culture doesn’t define the dying smoker’s senseless behavior as mental illness. What’s the difference? Does the fact that a man doesn’t admit to wanting to end his life relieve him of responsibility for doing so? The honestly suicidal woman is arguably more rational and clear than the smoker clouded in denial who works toward the same end.

Or consider delusions. If a man believes the CIA has implanted thought control devices in his brain, everyone agrees he is out of touch with reality; we call this paranoid schizophrenia. But if a political leader proclaims that environmental exploitation isn’t a problem, even as the ecosystem destabilizes, no one considers her delusion a sign of mental illness. Director Tom Shadyac’s delightful documentary, I Am, makes a similar point about how many of the values our culture promotes are actually insane.

What about obsessions? Someone who won’t leave the house without checking the doors and windows two dozen times earns a diagnosis of OCD. But a billionaire obsessed with accumulating ever more money gets worshiped like a modern deity.

Furthermore, psychiatrists dismiss highly positive spiritual experiences as delusional and hallucinatory simply because such states hint at phenomena that aren’t endorsed by materialist science. When for a time I entered what seemed like profoundly awakened consciousness back in 2000, I wasn’t congratulated. The psychiatrists labelled my experience a ‘manic psychosis’ and started me on Haldol. I was too trusting to doubt them at the time, but now I wish they’d referred me to a spiritual leader rather than the psychiatric ward.

Obviously, people spiral into all kinds of behavioral crises and need help. Sometimes they recognize their need for assistance, and sometimes not. But whether a particular maladaptive conduct gets labelled as mental illness or not has to do with cultural values, not medical science. If there weren’t so much stigma, and so much risk of over-medication, it wouldn’t matter. But a life may be derailed for years (or forever) after the hammer of a major psychiatric diagnosis shatters a person’s reputation and self-image.

Tradition tells us that the seventh century Korean Zen Buddhist Wonhyo achieved enlightenment when following an exhausting journey without water he collapsed at night in a deep cavern. He found an ivory bowl while groping in the dark, and relished the sweet water it contained with a rush of relief. But when he arose the next morning he realized he had reclined in a tomb. The ‘bowl’ was the cap of a human skull, and he saw that he had not drunk clean water but a putrified soup of decay. At first nauseated and repulsed, he spiritually ‘awoke’ shortly afterward when he recognized how what he thought about reality (and not reality itself) so decisively determined his experience.

The conditions we label mental illness are a bit like that, only in reverse. In my case a lifetime of profound sadness, plus the ministrations of countless therapists and doctors, convinced me that I suffered from a major psychological disease caused by my upbringing (which included early bereavement and severe child abuse) and genetic endowment (my depressed mother committed suicide). This view of myself had a major impact on my self esteem for much of my life, but I don’t believe it anymore. Now I understand that my sadness was a natural grieving reaction that may have been prolonged because no one validated my understandable sorrow after such a childhood.

No longer do I see my melancholy as the psychiatric equivalent of a decomposing skullcap. I now appreciate that life dealt me hardship early on, and I reacted normally. With time I overcame my grief, so that the traumatic past now stands as one of my most important teachers. Despite its ordeals, it led me to how I feel today: contented and more than a little knowledgeable about misfortune and its transcendence. The skullcap has transformed into the ivory bowl. Of course, neither perspective is necessarily ‘correct’ in any objective sense. But which picture I hold in mind has a powerful impact on how I feel.

I’ve already sketched how psychiatrists diagnosed as mania an experience that in another time and place would have been viewed as a divinely granted spiritual awakening. My epiphany landed battered and defamed in the charnel grounds of mental illness, when it could have been an elegant container of grace.

How experiences are framed determines how we feel about ourselves and how others view us. Does the frame of mental illness serve the majority of patients? Or does it more often sap vitality and confidence? I read in many blogs of the relief people feel when doctors finally define their problems as diagnosable mental diseases. I remember reacting similarly myself when a lifetime of moodiness finally earned me the ‘bipolar’ label. It felt so comforting to have my condition named and seemingly validated. But instead of decisively helpful treatments, the mental health system strung me along with decades of therapy and thousands of little pills, none of which improved my mood or outlook very much. It seems to me that if psychiatric diagnoses were truly valuable, they would guide clinicians to life-changing therapeutic choices. But how often do people diagnosed with ‘major mental illness’ leave the Psychiatry Department with an effective cure? Although they may feel transiently relieved, they and their family now must endure the burden of ‘knowing’ their minds are sick.

Only during the past few years, as I took up meditation and began exploring holistic methods of healing, did I begin to feel well. In fact, the change occurred rather quickly once I started meditating, tapered off the cocktail of psychiatric drugs, and quit hanging out at the mental health clinic. My once rock-solid conviction that my mind was ill gradually dissolved, and I began to wonder if I’m perhaps one of the healthier persons around, simply because I’ve worked so hard to achieve balance and peace. And if my ‘symptoms’ forced me into this growth, shouldn’t I be glad they afflicted me? Should I still consider my mental health issues as diseases, or were they gifts?

In many other cultures the kinds of malaise we define as medico-psychiatric illnesses are considered spiritual crises. In my own case, after fifty years of struggle with sadness and mood swings that never responded to conventional treatments but swiftly resolved with spiritual practice, I believe the mystical perspective to be more like the ivory bowl than what I heard within the mental health system’s well-meaning skullcap.

You may be dismissing all this as the ranting of a newly converted fundamentalist, but that’s not who I am. Although I believe spiritual transformation finally solved the problems that clinical psychology could not, I don’t hold any particular religious belief or adhere to any specific tradition. I don’t presume to know the nature of God or even to be sure of its existence. My own recovery convinces me that it is possible to find a ‘spiritual’ cure without abandoning reason or science. And that’s leaving aside the fact that modern physical theory describes reality in terms that sound essentially mystical.

In any event, a spiritual approach to mental wellness has little to do with ideas about God or the nature of reality. It has everything to do with how we see ourselves. If we think we are fragile and isolated personalities adrift among unfriendly and predatory human apes, we are likely to feel and act badly. On the other hand, if we see ourselves as sacred beings enmeshed in a grand tapestry of life and mutual interdependence, we feel uplifted and at peace. Which view is ‘correct?’ I don’t believe anyone can say. But I am utterly convinced that embracing the latter view is healthier than clinging to the former.

I’m not advocating the end of psychotherapy or the closure of mental health clinics. In fact, I like the phrase ‘mental health,’ because it describes what every human needs to strive toward. What I’m suggesting, however, is that we replace the DSM‘s ‘mental disorders’ paradigm with something less toxic. The Positive Psychology movement is one great improvement along these lines. A catalog of spiritual practices, written for mental health purposes, might also help. Many books are already on the shelves that describe how meditation can assist those suffering chronic emotional distress. A new standard for mental health care is emerging, but unfortunately the disabling and stigmatizing old one remains dominant.

Although the biomedical doctrine of ‘mental illness’ caters nicely to pharmaceutical interests, it serves patients poorly. Let’s give the skullcap a nice burial, and start over with some more elegant and uplifting concepts.

Copyright © 1992-2011 Psych Central. All rights reserved.

Site last updated: 21 May 2011